A recession is two consecutive quarters in which GDP falls. We are certainly headed for a recession. Some estimates are that GDP will not recover to its January 2020 level for a year or more. Will we have a depression? Unlikely. Words matter—and in economics, words are concepts. And as a famous philosopher reminds us, “Grasping a concept is mastering the use of a word.”

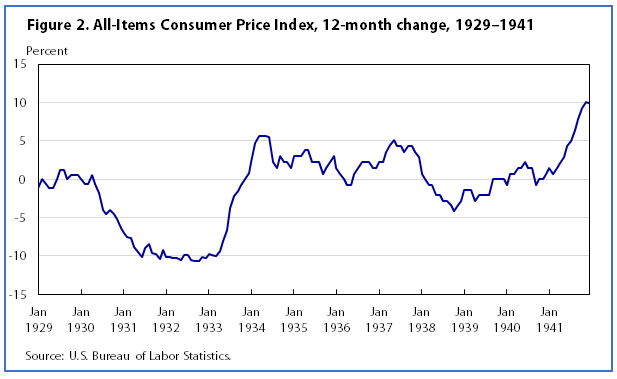

The term “depression” comes from a period in which prices are depressed—the general price level is falling or has fallen. Here is a picture of consumer prices from January 1929. Prices did not fully recover until World War II. But you cannot have a depression without depressed (falling) prices.

Are we facing a period of falling prices? Except for gasoline prices—the result of a Saudi- Russian game—few prices will be falling.

Ironically, the closure of so many businesses rules out falling prices. After all, prices fall when merchants have too many goods on hand and they wish to sell those goods to a population with too little income but an enduring demand for goods and services. Prices are reduced to encourage buying.

Unfortunately, once prices start to drop in this way, consumers hold off—expecting that prices might actually fall a little more tomorrow. This cycle continues as consumers delay, merchants panic, prices are reduced (sales, special offers,), etc. etc. Necessities are purchased, but many other purchases are delayed. Falling sales and revenues to merchants then induce them to reduce staffing, causing unemployment and further reducing aggregate income—and further feeding price cuts to encourage consumption. The economy falls into an under-consumption trap. Japan spent a decade or more in such a place during the 1990s and even into the recent past. It was a period of stagnation.

But the stay-at-home nature of this crisis has squashed demand for everything but bare subsistence—including toilet paper. Just think how much toilet paper is now sitting in the storage closets and back rooms of schools, restaurants, factories, movie theaters, and retail stores throughout the land. On the last day of work, the owners/managers of these shuttered places would have done all of us a big favor by sending each furloughed/dismissed employee home with a large bundle of toilet paper. But I digress.

To understand why we will not encounter a Depression, let me point out how very different this time is from the 1930s.

The period following World War I was one of exuberance and excess. Rural out-migration, fueled by technical change in agriculture spurred industrialization and optimism. The sense was that the stock market would go on rising forever. Sound familiar?

Agricultural production was robust leading to a drop in farm prices—creating rural despair.

In March of 1929 the Federal Reserve expressed alarm of excessive speculation in the stock market. Jitters produced some selling. Steel production started to decline as war-time levels of output began to fall. Construction slowed down a little, and car sales began to fall, furthering the decline in demand for steel (that is before cars were made of plastic).

But bank credit was easy and consumer debt seemed to be edging up. The stock market had been on a nine-year run that saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average increase in value tenfold. Sound familiar yet? There was a small correction in late September. The London Stock Exchange fell somewhat in September—and there was fraud involved. On October 24—so-called “Black Thursday”—the U.S. Stock market lost 11 percent of its value at the opening bell on very heavy trading.

This shock fueled fear of running out of cash and so many people rushed to their bank to withdraw funds. Recall, that was a cash economy—there were no credit cards. Most families held all of their liquidity in banks (or under the mattress). Some big-ticket merchandise was purchased on “lay-away.” The second phase, was therefore, a “run on banks” to get cash. By 1933, over 10,000 banks (almost one-half of the total) had failed. The supply of money had fallen by over 30 percent.

The third phase was evident—as purchases fell off, prices fell, and banks failed, many businesses were cut off from usual sources of credit. Unemployment grew. By 1933, almost forty percent of non-farm workers had lost their job. Farms and other businesses fell into bankruptcy. The recovery was sporadic and uncertain.

The fourth phase introduced something that is now familiar—a natural disaster. Widespread drought struck the major agricultural region of the country (the Midwest) in 1934—crops failed, more farms fell into bankruptcy, and food lines emerged. We did not have the storage capacity of today and so grain reserves were minimal. There were no global food chains bringing tomatoes, bananas, citrus, fish, and other exotics to the household. People ate meat and potatoes (recall dinner when you were growing up?).

The drought continued until 1940. The Dust Bowl further destroyed agriculture in the Midwest. Vast migration to California ensued. But economic conditions there were not much better. Even in those days, approximately 12-14 percent of the population lived on farms so they had access to some food. Even the non-farm population was still linked to the farm of parents or grandparents. Today, less than 1 percent of the population is on farms.

The memory of the Depression is one of unemployment, bankruptcies, and food lines. We did not have the policy instruments available to push money out to distressed families facing unemployment. So the Works Progress Administration put people to work.

It is from that experience that government programs were created to alleviate a repeat. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation assures us that our bank deposits are safe. Many other policy instruments are now available. However, we are learning just how clunky and slow they can be. One of the perils of a federal system, with strong independent states, is that we have 50 different political entities groping their way through this mess. Given sharp political divides, it is no surprise that responses vary. Apparently, states are forced to bid against each other to obtain essential medical supplies and equipment. European countries look upon us in disbelief.

So, we will not have a Depression, but we will now enter, I predict, a long period of suppressed economic activity. The definition of essential and frivolous consumption is up for debate.

Ostentation seems sure to go out of fashion. As I said earlier, Grey Eyed Athena is apparently repulsed by many of our lifestyle habits and choices.

I believe we might be entering a period defined as the “Great Suppression.” How does that sound?

Dr. Daniel Bromley can be contact at dbromley@wisc.edu.